By Amanda Westfall

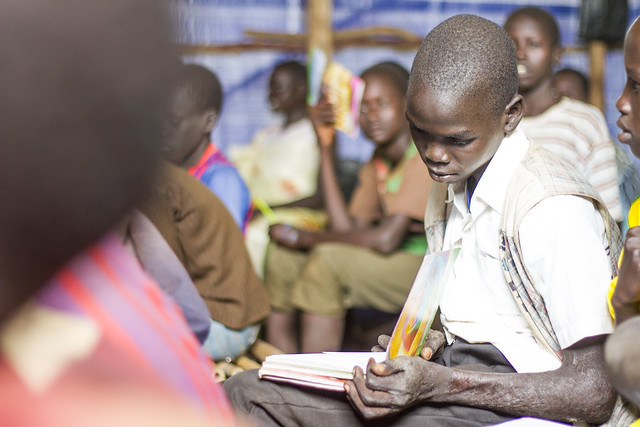

On 21 December 2017, eight-year-old Ethiopian Sefadin Yisak speaks about his friend on the hill, Adam, a nine-year-old, South Sudanese refugee boy. When boundaries, legal restrictions and cultural differences can divide communities, it is the children who remind us of the great importance of social integration.

Children truly know no borders. To Sefadin Yisak, an Ethiopian student at Tsore Arumela Ethiopian Primary School, Adam, a South Sudanese refugee who attends primary school within the neighbouring refugee settlement, is just his good friend. Sefadin doesn’t see the differences in history, culture or in the quality of educational services. He only sees the South Sudanese refugee boy as his good friend that he met at the river over the summer. They meet and play in the water with other neighbourhood kids when they don’t have school or other chores to do.

“To Sefadin, Adam (a South Sudanese refugee) is just his good friend. He doesn’t see the differences in history, culture or educational services.”

But from an adult’s perspective, it is evident that educational services have not been equal between refugees and their host-Ethiopian communities. With the host primary school only a 15-minute walk from the refugee settlement, one can truly notice the differences.

In addition to their struggle to survive and flee from conflict, the South Sudanese refugees experience lack of quality education due to unskilled teachers, overcrowded class sizes and exclusion from the national educational system and the services it provides. On the other hand, some refugee settlements have in some cases benefited from other services, including better-constructed classrooms, play equipment and materials for teaching, while the host communities often experience a lack of funding to improve classroom infrastructure and educational materials.

Thus, these inequalities in educational provisions can create social barriers that could potentially build unnecessary tension between communities. In reality, there are more similarities between the communities than differences, such as language, food, family customs, and a passion for education.

When South Sudanese people residing in Ethiopia for multiple years (some over 20 years, some less than one year), and children from both communities – like Sefadin and Adam – show us the importance of integration, it is crucial to support this clear demand.

Sefadin says that his favourite school subject is mathematics because his 2nd grade teacher, Ahmed Mustefa, is very helpful. Ahmed explains the importance of integration with the refugee communities. He noted that the communities never lived in conflict, but that the lack of integrated services has limited the amount of authentic social interaction with the refugee community who live just a short walk away. He adds, “We are all human beings and when we live together it is better for socialization.”

“We are all human beings and when we live together it is better for socialization”

Institutions recognize the need

Institutions have started recognizing the need, and in response have begun providing services that support integration. With the support of the United States Government (US-BPRM), UNICEF has been working with partners – the Ministry of Education, the Administration for Refugee and Returnee Affairs, UNHCR, and Save the Children – to bring equitable and efficient educational services that spark social cohesion for both communities.

Refugee and Ethiopian teachers join the same training programme

Ahmed’s teacher training programme is a prime example. In his region of Benishangul-Gumuz, 149 refugee teachers and 225 host-community teachers have all taken part in the new UNICEF-developed teacher training flagship programme, Assessment for Learning. This new approach shows teachers how to implement continuous assessment techniques to better understand the learning gaps of children and respond accordingly.

It is the first of its kind – where refugee and national teachers learn the same skills at the same time. Ahmed and other teachers from both communities stayed in the same dorms for the 10-day course, learned from each other, and now feel more part of each other’s communities. Before this training, refugee and national teachers never interacted professionally. They were trained with different programmes, and in most cases, it was the refugee teachers who missed out on professional development and teacher enhancement opportunities. Now, with more equality in refugee and host-community teachers’ knowledge and skills, Ethiopian students, like Sefadin, and refugee students, like Adam, both benefit from teachers who were trained in the same teacher training programme.

Integration through sport and play

What’s most exciting about the integrated response is the development of sport and play activities. Both communities now enjoy new play equipment and learning and play materials such as balls, toys, puzzles, counting blocks, and others. Teachers are trained on the “Connect, Reflect, Apply” approach, to develop useful life skills in children. Both Sefadin and Adam now have new equipment to play and are learning the same life skills, in addition to enjoying the benefits of new solar-powered TV’s that display educational programmes.

More efforts are necessary for sustained integration

While some refugee settlements in Ethiopia have experienced integration, in terms of students attending the same school, teacher training integration, or social cohesion through extra-curricular activities, many communities still lack support for equitable integration.

Communities have started to integrate, whether it be working for each other during harvesting season, inter-marriage, or making friendships while playing in the river. Even Sefadin’s family is now supporting Adam’s family with food provisions, like sorghum, maize and mango.

It is time to truly respond to the needs on the ground. Ahmed insisted that “we need more programmes like these for integration,” as he reflected on his new friendships he developed with refugee teachers from the training programme. And young Sefadin adds that it would be “cool if Adam were in my class.”

When boundaries, cultural differences, and varying educational services can divide communities, it is the children – like Ethiopian Sefadin and South Sudanese Adam – who remind us of the great importance of social integration.

UNICEF continues to work with partners to implement programmes that spark integration of refugees and host communities in all five refugee-hosting regions of Ethiopia so that cross-cultural friendships, like that of Sefadin and Adam, can be supported with an equality in educational services.